Kaboom!

Before the young man could realize what he’d done, a tamping rod half his size blasted through his left cheek, exited the top of his skull, and landed a train car’s length away from him.

The year was 1848. The place was a railway construction site in Vermont. The man was Phineas Gage.

What happened next would forever change our understanding of the human brain. Immediately after the explosion, Gage acted like the clean-cut hole in his skull was just a scratch. He walked toward the nearest cart, drove into town, and saw a doctor. And as if this wasn’t enough, he joked about his injury.

“Here,” Gage told the doctor, “is enough business for you,”

Gage recovered miraculously — without speech, motor, or memory impairments. But something had changed. In the aftermath of the injury, the once clever, conscientious, reasonable young man became stubborn, unreliable, and disrespectful. His colleagues later remarked he was “no longer Gage.”

This may seem like an extreme, outdated case. But in today’s age of loneliness, many of us (myself included) have experienced our own versions of the Gage incident. When loneliness impairs our brains, we think less clearly, lose self-control, and empathize less. And while the impact of loneliness on the brain is less destructive than a pointy steel rod, it’s far more sneaky. Either way, the symptoms are the same: we lose part of what makes us human.

When your brain is on loneliness, you’re no longer you.

What Loneliness Does to the Brain

But let’s start at the beginning. Long before loneliness changes our perception of the world and drives us into a negative feedback loop, something far more fundamental happens:

Loneliness inflicts the brain with pain.

This may seem a bit odd. But think about it — what are some of your most painful memories? What I think of aren’t the moments I tore every muscle fiber in my left thigh or snapped my wrist after falling off my bicycle.

Instead, I think about heartache. I recall the times I was desperate for human intimacy during the pandemic or the moment I confessed my feelings to someone I deeply fancied — and got rejected.

In other words, the most painful moments of my life weren’t physical. They were social. Or rather, un-social. Lonely.

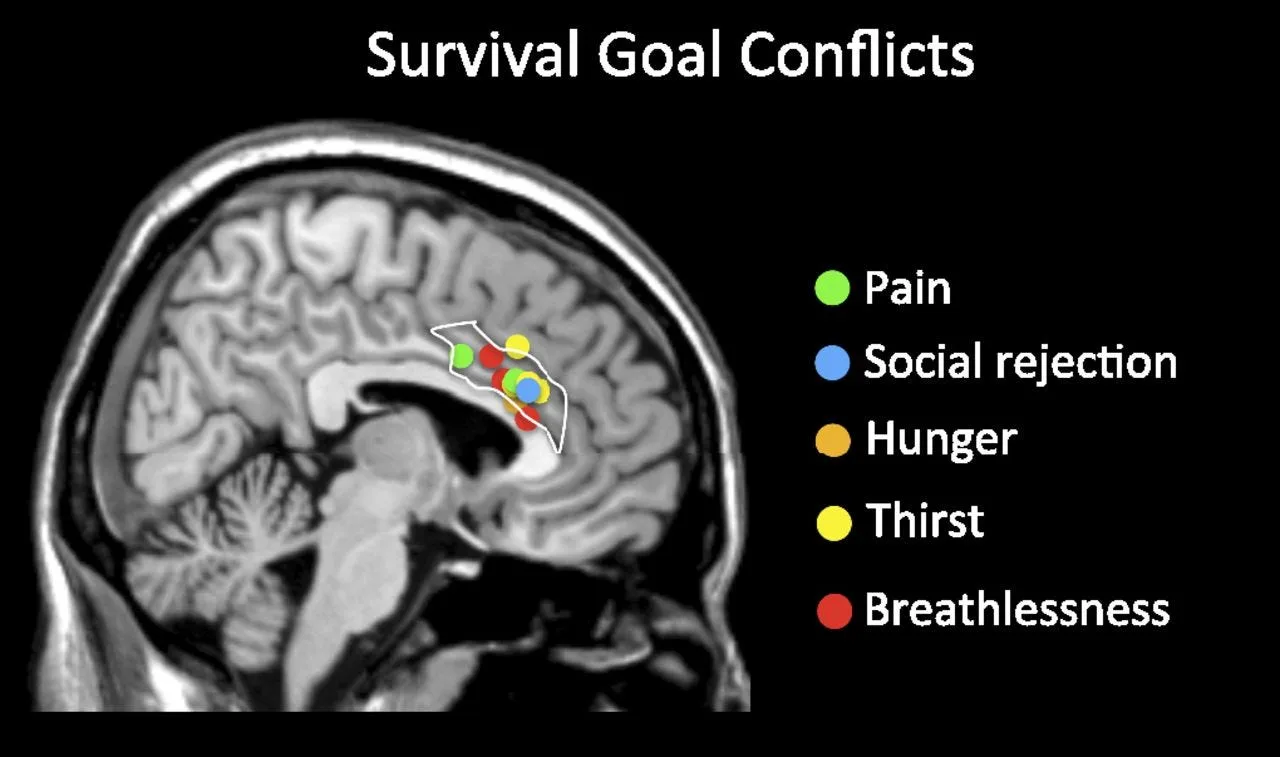

But surely, when we talk about broken hearts, grief, and exclusion — we just use pain as a metaphor, right? Well, not quite. Neuroscientists found that social rejection lights up precisely the same brain areas as physical pain, hunger, thirst, and breathlessness. And not just that: the worse people perceive social rejection, the stronger they feel this pain.

Of course, social pain may feel different from physical pain. But modern brain scans prove what tragedies, ballads, and paintings have been trying to tell us for centuries. The pain of loneliness is just as real as a punch in the face. It’s as stressful as having no access to food or fresh water. It’s as frightening as drowning in a deep, dark ocean.

So, why is that?

And perhaps more importantly: why don’t we take loneliness seriously despite the pain it inflicts?

To answer these questions, we must first understand the central organ of loneliness: the social brain.

The Pain and Gain of the Social Brain

Being social is so vital for human survival that our brains have evolved a neural network purely dedicated to social thinking. Neuroscientists call it the social brain. Thanks to this upgrade in our brain software, we can rapidly recognize minuscule facial cues, understand social hierarchies, navigate social norms, and read minds. Yes, read minds. Our brains are hyper-tuned to read emotions. This goes so far that we search for facial cues in everything we encounter.

Look at the two cars below. Chances are, they aren’t just cars to you. Our meaning-making social brains transform them into vehicles with personalities. To me, the first car is fierce, sharp, and aggressive, while the other car is bold, open, and dull.

In short, the social brain loves being social. That’s why we find it so fascinating to see our friends on social media and why everything we create is social. But it also explains why loneliness and social rejection are such painful experiences. Just like physical pain signals a twisted ankle, social pain signals missing social support. Of course, from today’s perspective, social pain doesn’t seem to serve us in the way that, say, a growling stomach makes us grab a bite to eat. It’s tempting to think that loneliness is merely a bug in the human brain.

But the social brain proves it’s the other way around.

Loneliness isn’t a bug. It’s a superpower. Social pain is arguably the number one reason why humans have built societies, rocketships, or the Taj Mahal. See, an isolated homo sapiens is fragile. Helpless. An easy snack for lions, bears, and other predators. But add two, three — add thousands, millions of homo sapiens — et voilà, here we are, at the top of the food chain. And all along, social pain was our compass: it made us seek out community, cooperation, and strength in numbers.

Life without loneliness would therefore be the equivalent of having no appetite. We would wither like plants without water. Loneliness is the glue of humanity.

And yet, we still underestimate the magnitude of the social brain.

What Maslow Got Wrong

One theory might encapsulate why we stopped taking the social brain and its pain seriously.

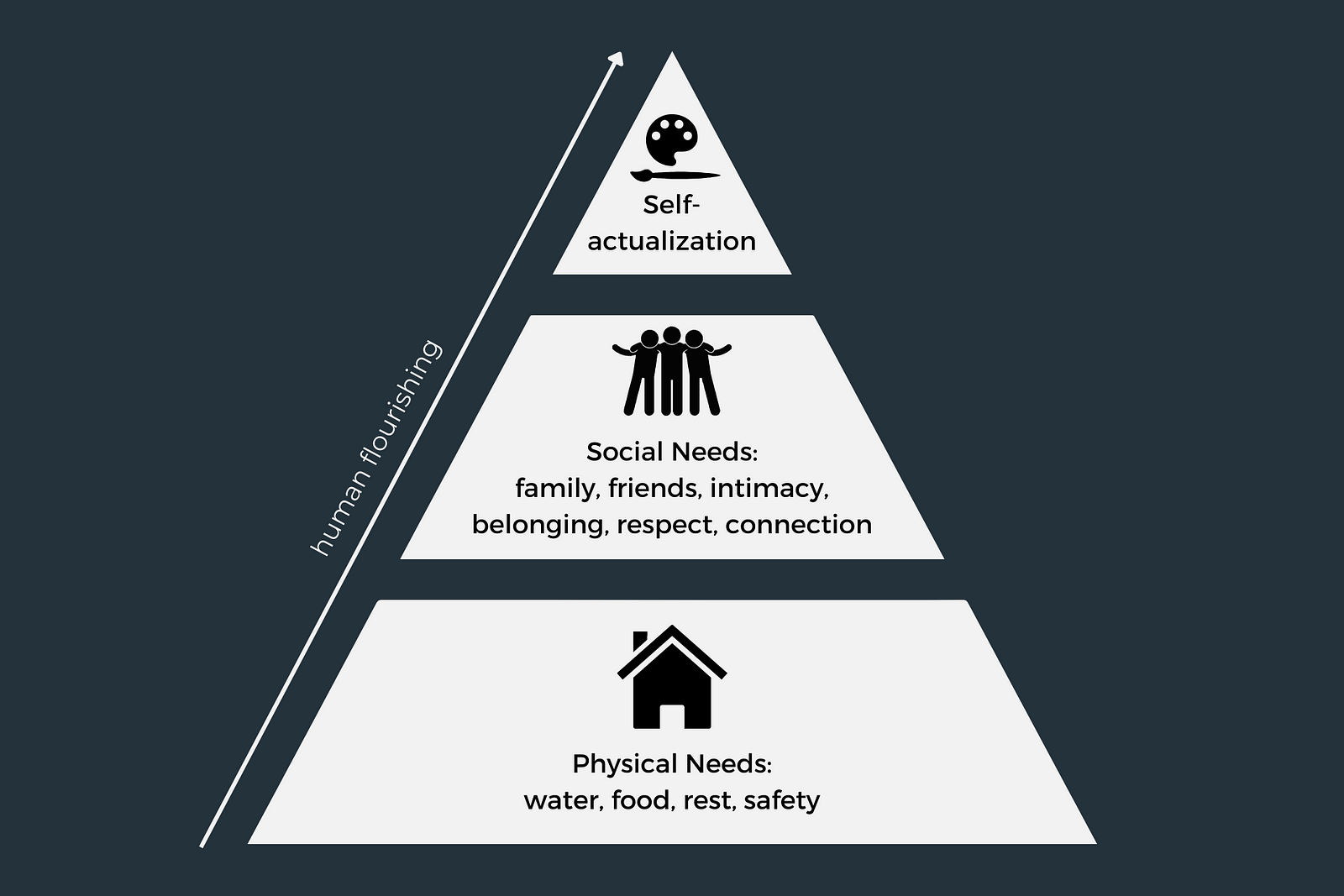

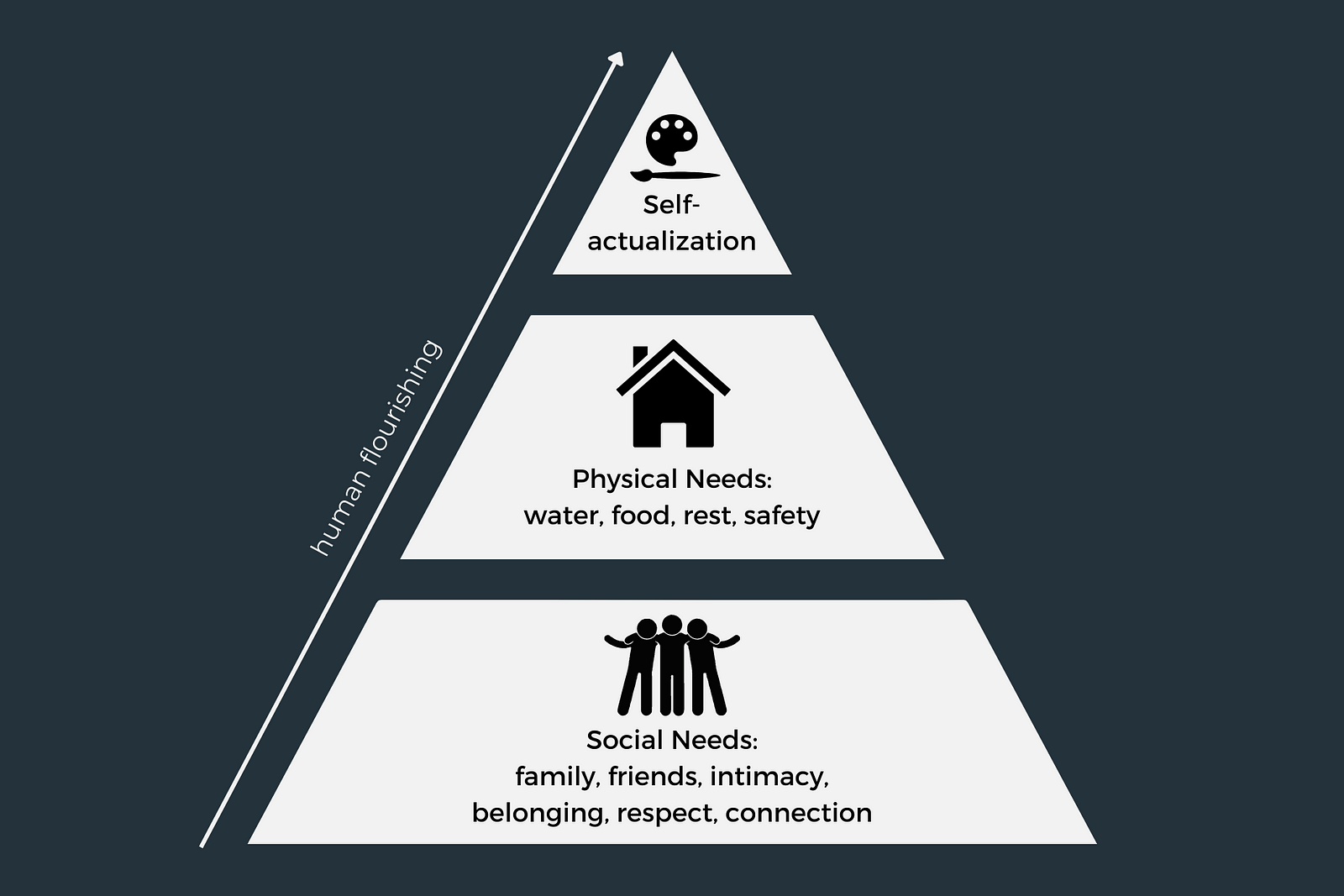

This theory is best known as the hierarchy of needs and was introduced by psychologist Abraham Maslow. Often illustrated as a pyramid, the hierarchy describes the stages of human flourishing. First and foremost, according to Maslow, we must secure physical needs (food, water, shelter). Only then can we move on to pursue social needs (relationships, community, social esteem). And finally, on the top of the pyramid lies our need for self-actualization.

It’s a neat concept. Except… Maslow got it wrong.

The most fundamental human needs aren’t physical. They’re social. Seems odd? Well, think about the first years of your life. How long could you have survived without care, nursing, and protection from others?

You couldn’t have.

Humans, more like any other mammal, are born unfinished. It takes us two decades to develop our brains and grow our bodies. And until then, we heavily rely on social ties to guide us through danger, hunger, and coldness. Therefore, social connection is the foundation of our survival. It’s the condition for our very existence.

What does this teach us?

Loneliness isn’t just another survival mechanism like hunger, thirst, or physical pain. It’s the ultimate survival mechanism. And again, that’s why loneliness is so painful. It’s how our socially wired brains tell us, “Hey! You’re a social being with social needs. But right now, I don’t feel connected. Let’s do something about that!”

This raises a crucial question: What if we ignore social pain and loneliness? What if we can’t meet our social needs?

Turns out, we become less like ourselves and more like Phineas Gage.

How Loneliness Changes the Brain

Phineas Gage died twelve years after his brain injury. The accounts of his life after the incident are fractured, but his skull and iron rod have been preserved until today. Which has allowed neuroscientists to study Gage’s unique brain and how it affected his personality.

What they found was shocking yet revolutionary.

Brain models show that the iron rod destroyed Gage’s left frontal cortex and its neural wiring. This finding is important because the frontal cortex is basically what makes us human. It’s not just responsible for self-control and decision-making. It’s also part of the social brain and thus enables us to empathize, process emotions, and interpret social signs. What’s really surprising about Gage is that he functioned without his frontal cortex. Yes, he became unsociable, selfish, impulsive, and “no longer Gage.” But he functioned.

Ready for a curveball?

When we struggle with intense loneliness, we experience similar brain impairments to the ones Gage experienced after his injury. We still function. But — often without noticing — we lose the part that makes us human.

As John Cacioppo and William Patrick write in their book Loneliness:

“[W]hen social exclusion appears absolute and unyielding, the aversive feeling of isolation loses its power to motivate us. Instead, it seems to disturb the very foundation of the self.”

The “aversive feeling of isolation” here is simply the social pain we discussed earlier.

This next part is crucial: if we recall that the “foundation of the self” is to be social for humans, it only makes sense that this foundation crumbles when we’re lonely. The social brain gets deprived of social needs. And when that happens, the entire pyramid of human flourishing comes crashing down. What remains is a last-resort strategy to preserve one’s identity and survival: selfishness.

Cacioppo and Patrick again:

“… feelings of isolation can cause declines in executive control and self-regulation that lead to impulsive and selfish behavior. The ability to respond actively and purposefully also declines, replaced by passivity, negativity, and sometimes even clinical depression.”

All these effects trigger a snowball effect — the loneliness loop — that corrupts how we perceive the world.

“… loneliness assaults both our self-restraint and our persistence. It distorts cognition as well as empathy, in turn disrupting other perceptions that contribute to social regulation.”

So yes, we still function under severe, chronic loneliness. But, like Gage, we become more like cold-blooded machines, like shells without a soul. We lose self-control, empathy, and our sense of joy.

But why would our brains do such a thing? Why would they self-sabotage? And how does loneliness manifest itself in the brain?

Why and How Loneliness Can Sabotage the Brain

The features of a lonely brain may look like self-sabotage from the outside. But the brain’s hostility, hypervigilance, and negativity are actually forms of self-preservation. It’s similar to how our brains learn from physical pain. When we touch a hot stove, we learn to be more careful next time and eventually avoid it altogether. Similarly, social rejection scars the brain — first through developing negative biases, later through complete avoidance and withdrawal.

How does this play out?

These five mechanisms are worth noting:

- Hostility — Lonely brains apply a hostility filter to everything they experience. And unfortunately, this filter isn’t selective. It’s always there, like a lens stained from the inside. As a result, we become more sensitive to social cues but worse at analyzing them. We’re more likely to interpret neutral situations as hostile. When I feel lonely, I get bitter when someone doesn’t respond to my text messages. Objectively, this is a neutral situation (they might just be busy), but my lonely mind instantly concludes, Yup. They hate me now. I’m unlovable.

- Rumination — Another feature of lonely brains is that their default mode network is more active. The default mode network is the daydreamy, reflective state of the brain. And so, when we spend more time in this state, we’re more concerned with our inner world than the external one. So it’s not just that we become worse at interpreting social settings when we’re lonely. We also become more prone to overthinking those bad judgments. Unsurprisingly, loneliness is directly linked to depression.

- Deprivation— The lonelier we feel, the more difficult it gets to escape this mistrustful self-preservation mode. We perceive social interactions as less rewarding and pay more attention to people’s distress. As a result, we tend to experience less intimacy and physical touch during lonely periods. This deprivation is not just unfair but also unfortunate because we release less oxytocin — the very hormone we so desperately need to experience warmth, trust, and connection.

- Hypervigilance — The previous mechanisms culminate in a constant fight-or-flight response. The lonely brain is always on the lookout, always stressed, always scanning environments for malicious signs. As a result, social settings become dangerous, insecure, or something we must endure. For instance, I often remember panicking at parties when I felt lonely: What will they think of me? I’m sure I seem like an absolute loser to them. I don’t know anyone here — help!

- Otherness — Ultimately, lonely brains process the world differently. And this otherness may actually cause and intensify feelings of loneliness. We don’t just feel disconnected when we’re lonely. We also feel misunderstood.

So, what can we do?

How to Patch Up a Lonely Brain

There’s one last piece to Phineas Gage’s story that many reports leave out. And that’s just how miraculous his recovery was. Roughly three years after the incident, Gage started working as a long-range coach driver in Chile — a job requiring social and planning skills. This suggests that Gage must’ve regained some of his lost brain functions.

How was this possible?

Turns out, our brains are extremely malleable. They can shape, twist, and turn around all sorts of challenges. This ability is called neuroplasticity, and, as Gage’s story suggests, it’s powerful enough to patch up a literal hole inside the brain. As psychologist Malcolm Macmillan remarks on the case:

“Even in cases of massive brain damage and massive incapacity, rehabilitation is always possible.”

The fact that Gage recovered from one of the most horrifying brain injuries ever recorded — thus losing his social and decision-making skills — fills me with hope and confidence. I’m confident we can fill our hole of loneliness with meaningful connections— no matter how dark, deep, or scary it might seem at the moment.

Here are four techniques to heal a lonely brain.

- Take social pain seriously — This might seem obvious, but the way our society approaches loneliness suggests we still don’t take it seriously enough. We tend to prioritize a big house, a new car, and a glorious career over meaningful social connections. What adds to this is that loneliness is a deeply stigmatized emotion. We often prefer to cover it up on social media or numb it with distractions. So, just becoming aware that our social needs are literally the foundation for everything we do is a great start. Perhaps we’ll slowly grasp that social wounds deserve the same attention — if not more — than physical wounds.

- Flip over into para — Since loneliness activates the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight mode), one of the most effective things we can do about loneliness is to activate the parasympathetic nervous system (rest-and-digest mode). Julie Holland, psychiatrist and author of Good Chemistry, calls this “flipping over into para.” Here are three para-inducing activities she recommends: breathing for roughly 10 minutes, making exhales longer than inhales; doing yoga or any other activity that connects body and mind; and havening, a self-soothing technique where you hug yourself, stroking your upper arms over and over.

- Release oxytocin — If we had to pinpoint a chemical of connection, it would probably be oxytocin. Releasing oxytocin is, thus, the most natural antidote to loneliness and disconnection. We typically release oxytocin through physical touch — taking someone’s hand, hugging, kissing. But it’s also possible to release oxytocin by yourself. Studies found that music production (rather than listening) activates the social brain’s parts for connection. There’s also great evidence that exercise releases oxytocin. Don’t know where to start? Try singing or running — they don’t require any gear. Bonus points for choirs and team sports.

- Expect the best — I know this sounds naïve, but hear me out. The thing about loneliness is that it makes us demanding, critical, and passive. And, of course, it can feel risky and counter-intuitive to stop listening to these self-protection mechanisms. But it’s important to remember that they can become self-fulfilling prophecies. As in: the expectation that others won’t like you will lead to actual aversion. Conversely, trusting in other people’s reciprocity, goodwill, and kindness will actually evoke these qualities. Remember: the lonely brain misinterprets neutral signs. An unresponded text message can have thousands of causes — spontaneous hate is rarely one of them.

All of this takes time. Just like Phineas Gage didn’t immediately heal the cavity in his skull, we can’t expect to patch up our lonely brains within a week. Let’s take it one day at a time.

The road to connection is always under construction.

Perhaps all this was a very long-winded way to say that your loneliness makes sense. There’s a reason for your pain, your insecurity, your angst. There’s nothing wrong with you. Quite the opposite — intense feelings of loneliness are a wonderful trademark of being human. Feeling isolated doesn’t mean you’re a machine with broken parts. It means you’re a hyper-social creature with unmet needs.

And as always: loneliness and connection are two sides of the same coin. For every negative effect loneliness has on our perception and health, social connection has a positive impact.

Loneliness inflicts pain; connection soothes.

Loneliness makes the world hostile; connection makes it charming.

Loneliness impairs cognitive power; connection supercharges it.

Knowing what loneliness does to the brain helps us flip the coin. We begin to grasp why we suffer. What our real needs are. How our perception gets out of tune. And what we can do to fix it.

Phineas Gage recovered from a literal hole inside his brain. We’ll manage to fill the void of loneliness. One connection at a time.