When I was stuck in a deep rut and YouTube rabbit hole a few months ago, I randomly came across an interview with Dr. Anna Lembke — a psychiatrist, author, and addiction specialist. Unexpectedly, I heard her say something that pierced through my apathetic slumber:

“We’ve reached a tipping point where abundance itself has become a physiological stressor. So it’s not that we’re morally weak or lazy or even indulgent … It’s that the world has become a place that is mismatched for our basic neurology and physiology. And we’re trying to figure it out, but it’s super, super hard. And we’re getting sick in the process.”

Something clicked when I heard her say that. The world has become a place that is mismatched for our basic neurology. I found this message so timely that I didn’t just buy Dr. Lembke’s book, Dopamine Nation, but also made it the first pick of my book club, The Bibliosopher’s Club.

And yet, after reading Dopamine Nation for 45 days and spending roughly 15,000 words on chapter reflections, I can’t recommend this book. The science felt superficial. The stories bland. The advice half-hearted. It was like dipping toes into the water, stirring it around, and eventually deciding you won’t plunge in.

However.

Dopamine Nation was a catalyst for me. It wasn’t necessarily the book’s content, but the process of deep-reading it that made me think about dopamine, consumption, and our world of overabundance. Particularly, it propelled me to do something about my YouTube addiction that, at the time, glued me to a screen for hours, turbo-charged my numbness, and drained my motivation like a vampire.

So, here are five lessons and one surprising conclusion from deep-reading and book-clubbing Dopamine Nation. We’ll talk about dopamine, pain, and pleasure — and how the crucial link between them ended my YouTube addiction.

1. Why Chasing Pleasure Can Make Us Miserable

One of the protagonists in Dopamine Nation is David. His problem is simple yet far-reaching: David medicates himself at the slightest sign of discomfort. Paxil for anxiety, Adderall for brain fog, Ambien for sleep. As he tells Dr. Lembke: “In the end, it came down to comfort. It was easier to take a pill than feel the pain.”

My “pill” was (and still is) YouTube and other streaming services — Netflix, Amazon Prime, you name it. I got sucked into the tube, and the tube sucked any remaining grit out of my system.

I felt numb.

But it’s not just video entertainment. The amenities of modernity have made my life so comfortable that I shriek at the first sign of unease. I want to fix it. As in: Make it stop!! When I’m tired, I want coffee. When I’m in pain, I pop a pill of Ibuprofen. When I’m bored, uncomfortable, or worried, I frantically check emails or my latest blog post’s stats.

But here’s the ultimate question: Is this a bad development? Like, why shouldn’t we indulge in the things that make us feel better?

Well, Dr. Lembke raises some valid problems with pursuing whatever feels good in the moment:

- Dependency — The more we medicate/numb ourselves, the more we need that thing to function normally. David, for example, got to a point where he couldn’t go about his day without taking Adderall. And whenever he needed to study, he had to exceed his regular dose to feel the effects. Likewise, I felt a strange itch when I didn’t watch YouTube before going to bed or after waking up.

- Estrangement — When we always try to fight the symptoms, the root causes of our problems remain concealed. We stop listening to our actual needs. My itchiness, I later realized, wasn’t a call for more YouTube videos but a plea to stop overstimulating myself.

- A lack of self-control — Not everything that feels good is actually good. When we develop the hedonistic habit of indulging in everything that makes us happy in the moment, it gets darn tough to do the difficult stuff that fulfills us in the long term.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that, whenever I feel empty, I want to fill my body with food and shove entertainment into my mind. But, of course, this is rarely fulfilling — and it actually has the opposite effect. After the fact, I feel even more hollow, even more empty. Which, in turn, fires up my cravings to fill that void.

So, why is that? What happens when we unleash the floodgates of Dopamine in the brain?

2. Dopamine Overdose: When Nothing Feels Good Anymore

First, we need to answer a crucial question: What is dopamine, really?

Dopamine is the most important neurotransmitter for processing rewards in the brain. When we eat chocolate, for example, dopamine bounces between neurons, the brain’s main functional cells, to reinforce this behavior. Contrary to popular belief, dopamine isn’t so much involved in the pleasure of a reward. It’s more about the incentive to get that reward. “Wanting more than liking,” as Lembke puts it. Without dopamine, we could still enjoy things, but we would lose any motivation to pursue them.

Because of its reward-centric role, we can use the amount of dopamine a drug releases in the brain to measure its addictive potential. The more and faster a drug releases dopamine in the brain, the more likely we are to get addicted to it.

In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Lembke uses the metaphor of the pleasure-pain balance to explain our brain’s dopamine levels. Like any balance, the pleasure-pain balance wants to remain, well, balanced. So, when we experience X amount of pleasure (by indulging in things that feel good), the balance will tip over to pain afterward, thus invoking X amount of pain.

But as we’ve seen earlier, we can’t just pursue more and more pleasure to crowbar the balance to pleasure. This will backfire. Here’s how Dr. Lembke puts it in Dopamine Nation:

“With repeated exposure to the same or similar pleasure stimulus, the initial deviation to the side of pleasure gets weaker and shorter and the after-response to the side of pain gets stronger and longer …”

In other words, the relentless pursuit of pleasure breaks the pleasure-pain balance’s equilibrium. The pain side gets heavier and heavier — as if someone attached weights to it. As a result, we need to consume more indulgences to experience the same amount of pleasure we once achieved with a small bite. We also become more sensitive to pain.

When talking about addictive substances, this effect is called tolerance. For instance, the more YouTube I consumed (thus releasing more dopamine), the more videos I needed to feel entertained. They also needed to become more stimulating. I started with somewhat “enriching,” long-form content — videos on philosophy, BookTube, documentaries. But soon, this content stopped satisfying me.

Things escalated.

Here was a person making knives out of cardboard. Here were two guys dressed up as Crusaders, screaming at each other. Here was a one-hour analysis of Taylor Swift’s success story. I got to this point where I started one video, and a few seconds into watching it, I was already looking for the next one. And the next, and the next, and the next.

This overindulgence in pleasure can backfire dramatically. Lembke again:

“[H]eavy, prolonged consumption of high-dopamine substances lead to a dopamine deficient state.”

When people flood their dopamine receptors with addictive behaviors, they eventually lose the ability to transmit dopamine properly. This dopamine-deficient state is called anhedonia. It’s when nothing feels worth doing anymore. Complete apathy. Total numbness. The only thing that seems worth pursuing then is a high-dopamine substance — and even that will feel less satisfying.

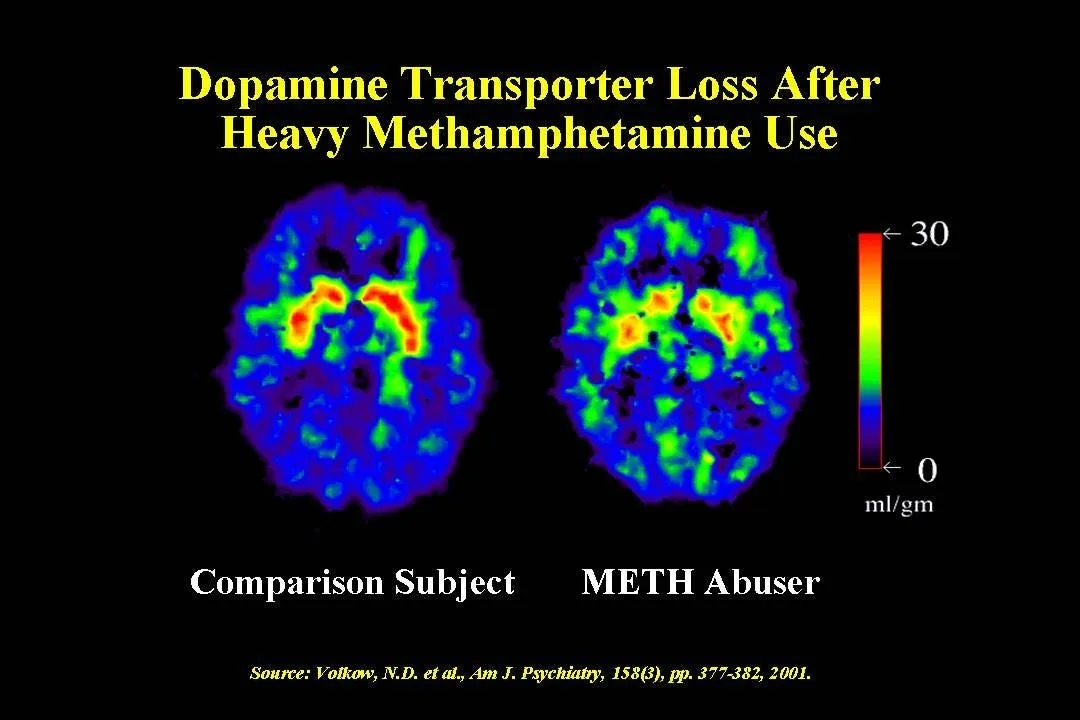

Below, you can see the dopamine activity in an average brain, and on the right, you see a brain exposed to heavy methamphetamine use. The person with the brain on the right needs their drug just to function. To feel normal. To level their pleasure-pain balance. Nothing feels good anymore. That’s what David experienced with all the medications he took.

Now, I know it’s suboptimal to compare high-dopamine drugs like methamphetamine to my YouTube overdose. But it may explain — to some degree — why I felt so empty, unmotivated, and mentally paralyzed. The YouTube videos were such an easy, abundant source of dopamine that they overflooded my receptors.

The good news?

If we can abstain from a drug, the brain can readapt to the drug’s absence. The pleasure-pain balance then naturally returns to a level state. As a result, we become, once again, more receptive and sensitive toward simple, organic pleasures — like having a nutritious meal, watching the sunset, or feeling the wind brush our skin.

Here’s how to reset.

3. An 8-Step Guide to Rebalance Dopamine Levels

Anyone who prescribes you a dopamine detox didn’t do their research.

A detox would imply that dopamine is a toxin in our body we must exude. But as we’ve seen, our bodies naturally produce dopamine. It’s only when substances or devices overclock our dopamine production that we run into problems.

We mustn’t banish dopamine. We must balance it.

That’s why, in Dopamine Nation, Dr. Lembke uses the term dopamine fast to describe the process of abstaining from behaviors that unleash high doses of dopamine. To get there, Lembke has devised an eight-step framework called DOPAMINE. According to Lembke, this framework applies…

“… not just to conventional drugs like alcohol … but also to any high-dopamine substance … we ingest too much of for too long, or simply wish we had a slightly less tortured relationship with.”

Here’s how it goes and how it applied to my experience:

- D = Data: What drug are you using, how much, and how often? This information helps you get a basic overview of the gravity of the situation. During my peak, I devoured YouTube videos for up to three hours per day, often before going to bed and after waking up.

- O = Objectives: What does the drug do for you? How does it help? These questions validate that there was once a genuine reason we started consuming a drug. Despite irrational behaviors, there’s always personal logic: we want to fit in, relieve uncomfortable emotions, kill boredom, the list goes on. YouTube helps me escape my own mind. It blocks out worries, insecurities, and boredom — however temporarily. It’s an escape. It’s a painkiller. It’s a reward.

- P = Problems: What are the drug’s downsides or unintended consequences? This might include problems related to health, morals, or relationships. The tricky thing is that we often cannot fully grasp these problems as long as we use the drug. I, for one, could feel the downsides. To name a few: brain fog, regret, lethargy, and bedtime procrastination.

- A = Abstinence: Stop using the drug for a month. Why one month? Lembke says this is the minimum time to reset the brain’s reward pathway. The first two weeks of this abstinence are usually the toughest because we start experiencing all sorts of withdrawal symptoms. But then it gets better. And if not, that’s also useful data because it means the drug wasn’t the cause of our problems. I liked this set of questions Dr. Lembke often asks her patients: “Do you still want to be using [this drug] like this ten years from now? How about in five years? How about a year from now?” Seeing my situation in the light of my future self helped me take action in the present.

- M = Mindfulness: Observe your thoughts, pain, and emotions. The unfortunate reality is that we won’t be able to block the pain of abstinence. Sure, there’s the quick fix to swap out the drug for a replacement — like going from cannabis to nicotine. But in the long run, this is ineffective as it keeps the pleasure-pain balance on the pain side. A better alternative is not just to endure the pain — but also to use it for practicing mindfulness. Whenever my YouTube craving returned, I asked myself: What is it really? Can I touch it? Where do I feel it exactly? What happens when I focus my entire attention on it? The itch was still uncomfortable, sure. But it lost its grip on me.

- I = Insight: How did the period of abstinence change your life? When we can manage to escape addiction, we see our behaviors — and perhaps our entire life — in a new light. I realized that quitting YouTube helped me propel into a “meta-abstinence.” I became more intentional about other indulgences — sugar, alcohol, overeating. This, overall, sparked unprecedented clarity, drive, and contentment.

- N = Next Steps: Do you want to keep abstaining or return to the drug? This may seem like a weird question, but Dr. Lembke suggests many people with mild addictions can return to using drugs in a controlled way. I’ve been dabbling with an approach of directing YouTube (rather than being directed by it) — i.e., I only consume content after figuring out a) what I want to watch and b) why I want to watch it.

- E = Experiment: What does your new life with(out) the drug look like? Moderation can often backfire. Not just for people with a past of severe addiction but also for the average person who’s exposed to an abundance of high-dopamine goods. This becomes particularly tricky with drugs that are vital elements of life, such as food, phones, or love. In my case, I need to access YouTube for a part-time job, so I’m still going through a trial-and-error process to find a sustainable solution.

Of course, all this isn’t easy. Abstaining from addictive behaviors takes more than spelling out DOPAMINE in capital letters.

So, what can we do to ensure we stay accountable? How can we develop a sustainable lifestyle when we’re constantly surrounded by easily accessible snacks of dopamine?

Let’s look at two strategies: self-binding and pain-pressing.

4. The Power and Necessity of Self-Binding

Self-binding is the act of hoisting intentional barriers between a drug and our (over-)consumption. The idea is to leverage one short moment of reason to improve our relationship with a drug in the long run. In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Lembke explores three types of self-binding:

- Physical self-binding: making it physically more difficult to engage in high-dopamine behaviors (e.g., switching off your phone and putting it in a different room).

- Chronological self-binding: limiting your consumption to specific time frames or milestones (e.g., only accessing YouTube after 5 pm or not smoking cannabis until finishing a project at work).

- Categorical self-binding: completely abstaining from certain categories of substances/behaviors (e.g., a vegan diet or absolute sobriety from alcohol).

Since I’m susceptible to visual cues — my phone lying next to me or seeing the YouTube app on my screen — physical self-binding has worked best for me. Here are two tactics I implemented:

- Building friction: Deleting the YouTube app from my phone, switching off my phone whenever I don’t need it, and putting it in a different room overnight.

- Self-protection: Installing app/website blockers on my laptop and phone, deleting my watch history and cookies so the algorithm can’t send me down a rabbit hole.

Self-binding rules can often seem constrictive. But actually, they’re liberating. By eliminating the behaviors that harm us and leave us feeling empty, we’re finally free to do — or at least think about — what we really want. Thanks to the rules we set ourselves, we can navigate a dopamine-overloaded world with reason, joy, and curiosity.

5. The Vital Discomfort of Pain-Pressing

What’s interesting about the pleasure-pain balance is that it works both ways. We’ve already seen that experiencing pleasure will trigger pain after the event. But the same can happen when we seek out pain in controlled ways: we feel pleasure afterward.

Typically, pain-induced pleasure feels far more satisfying and is released over longer periods of time than directly tapping into pleasure through high-dopamine goods. That’s why pretty much anything that feels worthwhile to us takes time and hard work.

A finished novel takes years of preparation, writing, and editing.

A healthy relationship builds on difficult conversations.

A runner’s high requires an intense run.

The most practical activities for pressing on the pain side include exercise, cold exposure, and meditation. The key is to find a pain level that makes you think, “Ohhh yep, this feels uncomfortable, and I really want to stop, but I also know I can safely keep doing it.”

This even applies to overcoming fears and anxieties. David, the protagonist we talked about earlier, struggled with social anxiety. After working with a therapist, he sought out social situations with increasing intensity and fear levels. At first, he just introduced himself to colleagues and asked them about their names. Soon, he could converse with any stranger — without the overwhelming fear, awkwardness, or nervousness.

How does this help with addictive behaviors?

For me, the satisfaction of pain-pressing puts everything in perspective. On the days I wake up early, go for a run, and take a cold shower, I’m literally a different person. I can think more clearly, get less itchy, and gain the self-control to do what matters most. Conversely, on the days I open YouTube after waking, I feel foggy, get moody, and chase easy pleasures. Which makes me feel regretful and slouchy.

But I’m not gonna lie: it’s been incredibly hard to make this switch. On so many mornings, I wake up greeted by my inner voice of indulgence: C’mon, just one video. You deserved it. You know you need it to relax.

Of course, I’m tempted.

One thing that has helped me is comparative visualization. First, I envision myself after consuming easy pleasures (like YouTube), then after hard-earned pleasures (like exercising). Finally, I compare the two.

Just becoming aware that I can actively influence my pleasure-pain balance like this has made a huge difference.

Conclusion: In Praise of Pleasure

Finally, I want to say something that Dr. Lembke has failed to explore in Dopamine Nation. Not all pleasure is bad. So many people consume Instagram, Netflix, alcohol, sugar, and other drugs in ways that feel healthy and balanced to them. They can live perfectly normal lives despite the drugs (or even because of them?).

After finishing Dopamine Nation, I thought, for a short while, that I needed to banish all dopamine snacks from my life: candy, wine, the new Black Mirror season, fast food, peppy playlists.

But I was missing the point.

If this book — and the overall neuroscience of dopamine — has a lesson to teach us, it’s not that we should categorically condemn pleasure. Rather, it’s that we should become more intentional about it. Life shouldn’t become a wicked prison cell of pain-pressing and self-binding. Sometimes, it’s just nice to dive into a mountain of candy or binge-watch all three seasons of The Boys (been there, done that).

The subtitle of Dopamine Nation is: “Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence.” This balance can be a perfect equilibrium between pain and pleasure. It can also be a series of alternating spikes between pain and pleasure. In other words:

Balance is how you feel balanced.

For now, I feel balanced by abstaining from YouTube as much as possible. But then again, part of the reason I suffered from my YouTube addiction was because a heap of self-help content brainwashed me into feeling guilty about it. And so, one day, I might break those shackles and enjoy indulging in YouTube while leading a life of contentment.

If we’re urged to find moderation in a world of abundance, moderation can also become an addiction. So perhaps we can dare to find moderation not just in pleasure… but also in moderation itself.

Want to Get More Out of the Next Book You Read?

If I learned one thing from studying philosophy and devouring hundreds of books, it’s this: reading books in a community supercharges your ability to extract their wisdom. That’s why I started The Bibliosopher’s Club, a book club where we explore what it means to live a good life – one book at a time.

Enter your email below to join hundreds of avid readers on our quest to read and live better.